After years of talk, MLS finally put their money where their Balaklava is and voted to change the league calendar from a “Winter-to-Fall” to a “Summer-to-Spring” model.

The current schedule sees the MLS regular season begin in early March (recently as early as February) and end in October. The new calendar, set to begin in 2027, would begin in July, with the regular season ending in May. This much more closely aligns with the calendars of most European (and global) leagues.

In the lead-up to the decision, prominent figures were clamoring for the switch, citing ambition and global legitimacy.

There’s certainly something to be said about that aspect of the change. Part of the league’s struggles to establish global supremacy no doubt has to do with the fact that players coming from the most talent-rich clubs/areas in the world either need to join MLS part-way through their previous club’s season OR part-way through their new club’s season.

The degree to which that affects player decisions to come to the U.S. is unknown, but it’s almost certainly a factor. More alignment, it stands to reason, should mean better access to talent.

And MLS could really use some better talent.

Soccer is currently thought to be just the 4th most popular sport among fans in the United States, with MLS even struggling to captivate fans in the U.S. to the same degree as Liga MX or the English Premier League. The gamble MLS is taking here is that switching calendars will lead to an increase in on-field quality and, in turn, to increased fan interest.

And that’s not a gamble without stakes.

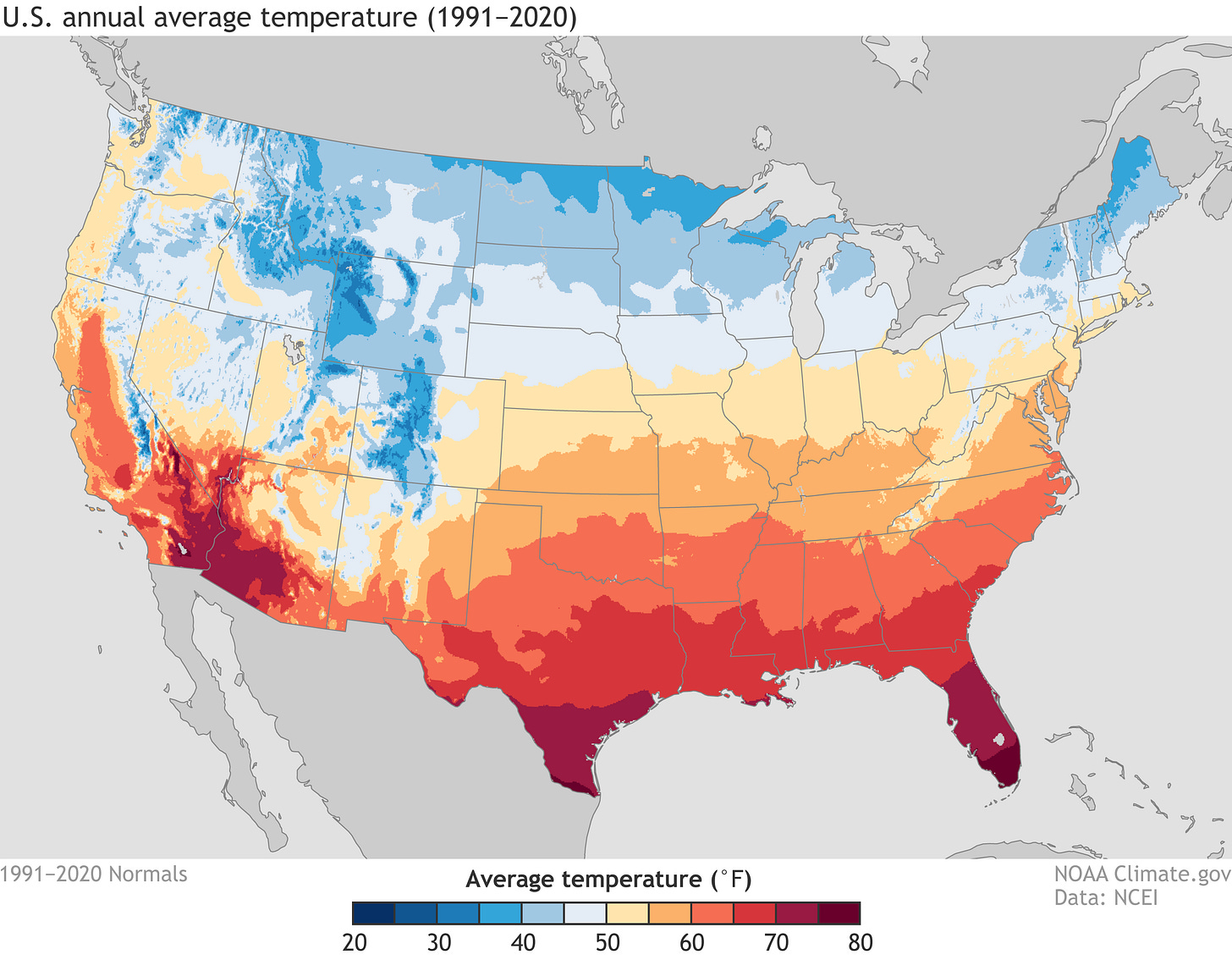

This is a map of the average temperatures in the United States, with data pulled from NOAA’s “Climate Normals” dataset.

I won’t link a full map of MLS teams but a quick cross reference here indicates that about 12 teams (9 U.S.-based clubs and the 3 Canadian clubs) play their home games in states that are predominantly blue on this chart - IE below the median average temperature. That amounts to 40% of the league’s clubs.

It would seem fairly straightforward that shifting towards more games in the fall/winter would have somewhat of a cooling effect on the league’s attendance, particularly for those 12 cooler weather clubs.

Woah, Woah Hold On

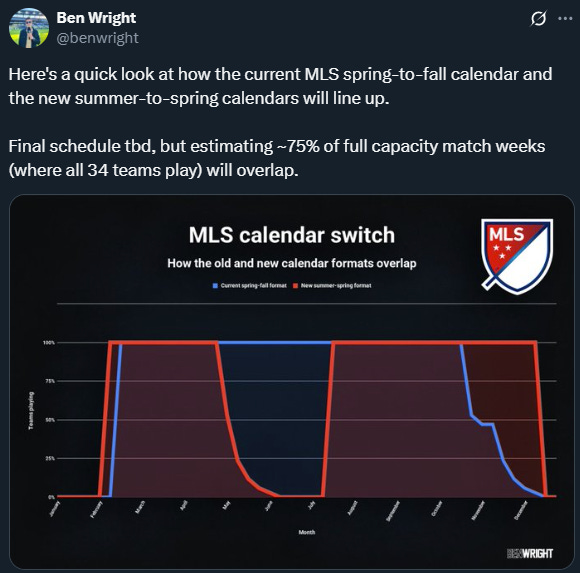

Don Garber says 92% of the schedule would fall in “exactly the same window” as the current schedule. That’s a measly 8 percent difference, so quit your complaining! And besides, MLS will “limit the number of home matches in northern markets during December and February!”

Setting aside the fact that any new schedule would find it difficult to avoid substantial overlap with the current setup — your season plays in 9 of the 12 months of the year as is — the numbers are perhaps a bit misleading.

Furthermore, this doesn’t account for the concentration of games played at different times of the year. Even if games are played in February or November in either calendar configuration, eliminating games from the warmest months of the year (June/July) for clubs in the northern portion of the league is going to have a severe effect.

Why is Weather Data So Complicated?

To illustrate this point, I’ve attempted to determine the change in average temperature that a Revolution fan would expect to experience under the new calendar. I will caveat the following analysis with the fact that I’ve had to make a number of assumptions.

The first set of assumptions comes from some of the language surrounding the league’s calendar change announcement, IE what exactly is “late February” or “mid-to-late July”. Compounding this issue is that the newly proposed calendar takes a “midwinter break”, doubling the number of nebulous start and end dates I had to guess at.

As a first pass, I did my best to approximate season and midwinter start/end dates based on the verbiage used in the release. I then directly shifted the Revs’ 2025 schedule to fit into that new window. That’s to say the first game in 2025 (Feb 22nd) was shifted to the 3rd weekend of July. The next game — a week later — was shifted to the following week in July and so on. For games that would have fallen during the “midwinter break,” I shifted games either backwards into Dec/Nov or forward into Feb/Mar. The most games the Revs played in any given month this year was six, so I used that number as my limit when shifting.

This isn’t going to be a perfect approximation of the proposed schedule, but it should be enough to give us a picture. I then counted the home games assigned to each month and plotted them below.

As a second pass, I used the new season footprint established by the vague definitions above, and tried to create the warmest possible schedule. Given a recent comment that “league’s principle is to not have a team play more than three games in a row on the road or at home,” I have attempted to follow that rule. Once again, I plotted the number of home games per month.

Keep in mind, while reading the above charts, that under the new calendar, an MLS season would take place during two calendar years beginning in the summer and continuing to the following spring so they end up reading a bit differently.

At first glance, it’s clear that the “direct shift” model provides a more even spread of home games throughout the season. It even gives the impression that the number of games in each month is roughly similar to the current schedule. How much worse could the weather really be?

It’s now, dear reader, that I must inform you that I have absolutely no background in meteorology. My understanding of the weather is more of the “red sky at night, sailors delight” variety. I regularly leave the house (with no umbrella of course) and step directly into a downpour.

I say these things to soften what I’m about to tell you. Finding historical weather data (you know, the constantly updating thing that is available in our pockets at any time — except for the past) is apparently kind of complicated. As it turns out, keeping the dozens of data points that comprise “the weather” - for every place, and for every minute of the day presents something of a data storage problem.

I’ve had to rely on several sources of weather data to even cobble together decent monthly average numbers. I’ll level with you, I did use AI to make predictions of hourly data.

I know, I don’t like it either. Given the ask of determining the temperature at ~7:30-9:30 PM (when most MLS games begin under the current schedule), and given the fact that it’s hit or miss which weather radars keep data from which dates and times, it just made sense to let the robots have this one.

The monthly average temperatures I used below are hand calculated from Boston temperature averages. The “game time temperature” is an AI prediction averaging hourly data from nearby weather sources between the hours of 7 pm and 10 pm.

Unsurprisingly, it’s substantially cooler in the evening than the daily average, particularly in the winter months when the sun sets in the afternoon.

I took those average monthly temperatures and, using the expected number of home games per month, made a ‘season long’ average temperature, both with the daily averages (calculated) and the AI-generated gametime averages.

The first thing to notice is that the average gametime temperature drop for the direct calendar shift is substantial, about ~20 degrees. That’s a fair bit colder and that’s just the average. I think it goes without saying that individual games could get very cold.

Using the weather ideal shift, the temperature depression is much more muted. That’s a good thing!

But in order to attain those temperature averages, I had to arrange the schedule such that the Revolution played at home just once between the last week of October and the second week of March. That’s a period of ~20 weeks with a singular home game.

OK it’ll be cold. But won’t it be worth it?

MLS is taking a gamble by making this switch. They’re betting that an influx of talent, gained by aligning the transfer windows with other leagues, will bring in enough interest to overcome any potential game-day losses.

On a macro level, a lot of the northern clubs are likely to lose some ticket sales. That could be due to fans skipping out on individual cold weather games, reevaluating their need or desire for season-long tickets, or by simply falling out of a rhythm with a sizeable gap in the winter.

Maybe that doesn’t matter. Maybe clubs in warmer parts of the country make up for those losses. But, as I mentioned before, about 40 percent of the league plays home games in those colder weather markets.

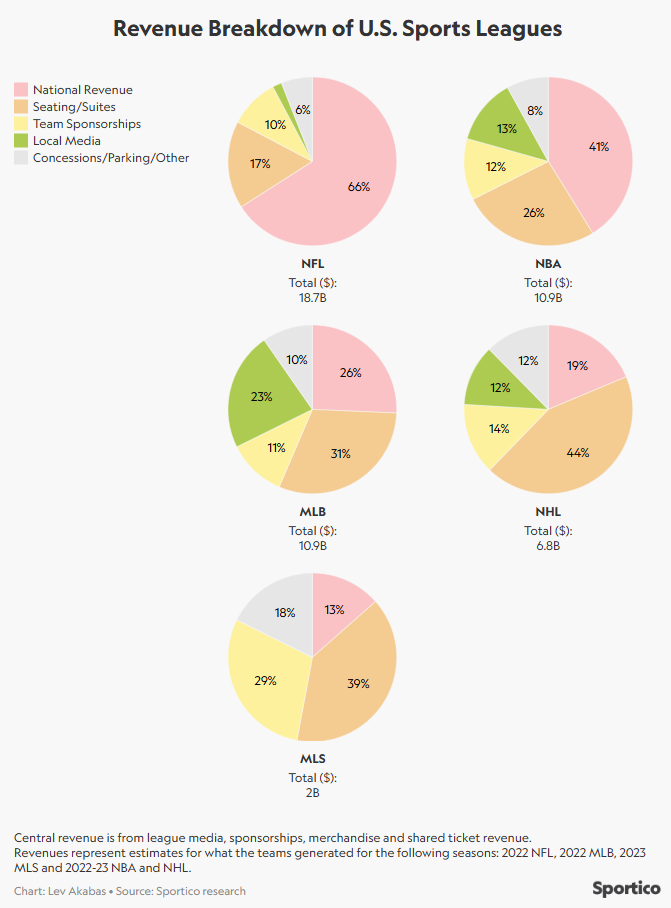

MLS, more than most other major U.S. sports leagues, relies on gameday ticket sales as a part of its revenue.

Disincentivizing fans from attending in person to a significant portion of teams for a significant portion of the season doesn’t feel like a winning strategy to me. Then again, we certainly can’t have people overseas not taking us seriously, can we?

Was there not talk of holding colder weather games in more warmer climates?